Description

1. The Genesis of African Mural Art: Ancient Rock Art

African Mural Art is a timeline of human expression that spans over 30,000 years. It traces a journey from spiritual communication on cave walls to geometric coding on village homes, and finally to the high-definition, digitally printed narratives of modern interior design.

Here is an overview of this evolution, categorizing the journey from the oldest rock art to contemporary digital wallpaper.

“Let’s go back to where it all began, stretching from as far back as 30,000 BCE right up to the 19th Century. In this era, the ‘canvas’ wasn’t fabric or paper—it was solid stone.

The artists worked with whatever nature provided, mixing ochre, charcoal, clay, and even blood to create their pigments. You can still see these incredible works today in landmark sites like the Drakensberg mountains in South Africa, the caves of Tassili n’Ajjer in Algeria, and at Brandberg in Namibia.”

Before walls were built, rock faces served as the first murals. This art was not merely decorative; it was deeply functional and spiritual.

San/Bushman African Mural Art

Often depicted as “trance dances” and the spiritual connection between shamans and power animals (like the Eland). It was a gateway to the spirit world.

Saharan African Mural Art

The massive African Mural Art in Algeria depicts a time when the Sahara was green and lush, featuring herds of cattle and giraffes, serving as a climate record of the past.

2. The Traditional African Mural Art: Vernacular Architecture (The Community Canvas)

“Moving on to a tradition that spans centuries and is still very much alive today. As communities began to settle down, the home itself became the canvas.

Instead of imported paints, artists used materials found directly in their environment—earth pigments, natural dyes, and even dung applied to mud walls. You can see iconic examples of this with the Ndebele in South Africa, the Kassena people in Burkina Faso, and across Ethiopia. For them, these murals were never just about decoration; they were a way to signal identity, show social status, and offer spiritual protection to the household.”

Ndebele Art (South Africa)

Perhaps the most iconic. Women paint their homes in striking, high-contrast geometric patterns. Originally, these designs were secret codes used to communicate during conflict with Boer settlers; today, they represent cultural pride.

Tiébélé Architecture (Burkina Faso)

The Kassena people decorate their windowless mud homes with intricate black (graphite), white (chalk), and red (clay) geometric patterns. These murals protect the house from rain and evil spirits while signifying the owner’s rank.

Ethiopian Orthodox Murals

Found within ancient rock-hewn churches, Ethiopian Orthodox murals serve as vibrant visual scriptures. Utilizing a distinct “flat” perspective and figures with large, expressive eyes, they vividly narrate biblical events. These murals were essential educational tools, conveying complex theological stories to a congregation that historically relied on visual and oral tradition.

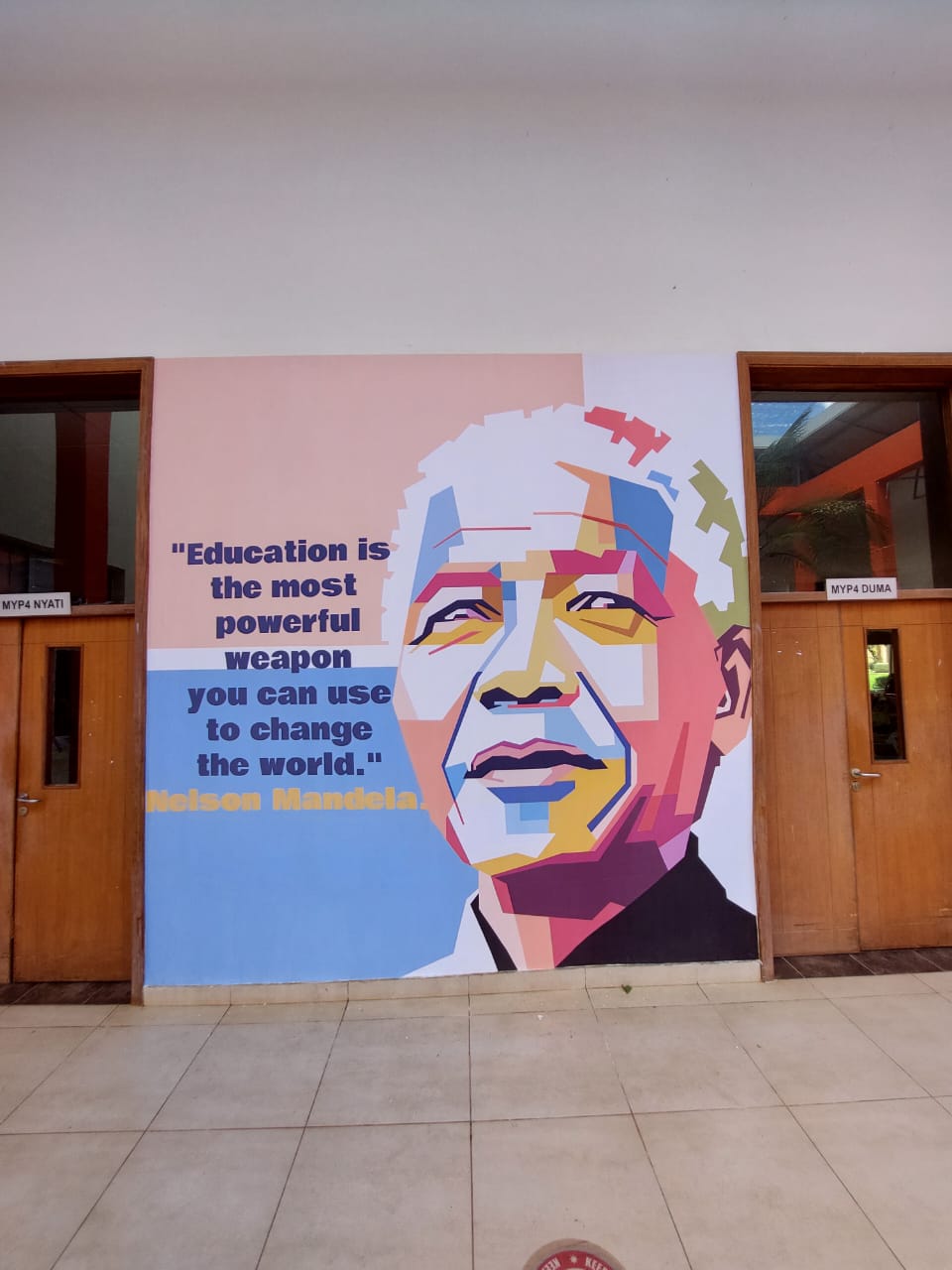

3. The Transition: Urban Street African Mural Art (The Political Canvas)

The transition of African painting from the “village compound” to the “city street” marks a shift from art as tradition to art as resistance.

In the late 20th century, as African metropolises exploded in size, the canvas changed from mud walls and bark cloth to concrete underpasses, railway sidings, and corrugated iron fences. This art form was not commissioned by elders to preserve culture; it was seized by youth to challenge authority.

Here is an exposition of how this art became Louder, Faster, and more Political.

Louder: Reclaiming the Public Space

Traditional muralism (like the Ndebele) was domestic and private. Urban muralism is aggressively public. It competes with commercial billboards and state propaganda, demanding to be seen by the masses commuting to work.

Dakar (The Set Setal Movement)

In the late 1980s, Dakar’s youth grew tired of the city’s decay. They launched the Set Setal (“be clean / make clean”) movement. They didn’t just sweep the streets; they painted them. Thousands of murals appeared overnight—portraits of Cheikh Amadou Bamba, Lions of Teranga, and civic messages.

The Shift:

It was a visual shout that said, “The state has failed to maintain this city, so we will own it.”

Cape Town (District Six & Woodstock)

In a city scarred by spatial apartheid, murals became a way to mark territory that had been erased. In District Six (a neighborhood bulldozed by the apartheid regime), murals serve as “memory markers,” screaming the existence of a community that the government tried to silence.

Faster: The Art of Immediacy

Unlike traditional painting, which follows centuries-old patterns, street art reacts to the news cycle. It is “fast media”—executed overnight to respond to a scandal, an assassination, or an election before the authorities can scrub it off.

Nairobi (The “Mavultures” Era)

In the early 2010s, graffiti became the primary opposition party in Kenya. Activists like the Mau Mau Collective and Boniface Mwangi (Pawa254) began stenciling murals of “vultures” (representing greedy politicians) on public walls in the Central Business District.

The Speed:

When MPs voted to increase their own salaries, murals mocking them appeared within 24 hours. This speed allows the art to shape the public conversation in real-time.

Lagos (#EndSARS)

During the 2020 protests against police brutality, the walls of Lagos (particularly around the Lekki Toll Gate) became instant memorial sites. Artists painted the names of victims and the blood-stained Nigerian flag. The art didn’t just record history; it mobilized the protest while it was happening.

Political: The Wall as a Weapon

This is the defining characteristic of the transition. The content shifted from geometric abstraction and folklore to biting satire and direct confrontation with the state.

The “Writing on the Wall”

In many African cities, the press is censored or self-censored. The wall is the only uncensored outlet.

Satire:

In Kenya, the matatu (minibus) culture acts as mobile street art. While often decorative, they frequently carry subversive portraits of figures like Tupac, Malcolm X, or local whistleblowers, subtly aligning the working class with global revolutionary figures.

Sanitation as Politics:

In Accra (Ghana) and Dakar, murals are often used to shame public urination or dumping. While this seems minor, it is deeply political—it is a critique of the lack of public infrastructure and a demand for civic dignity.

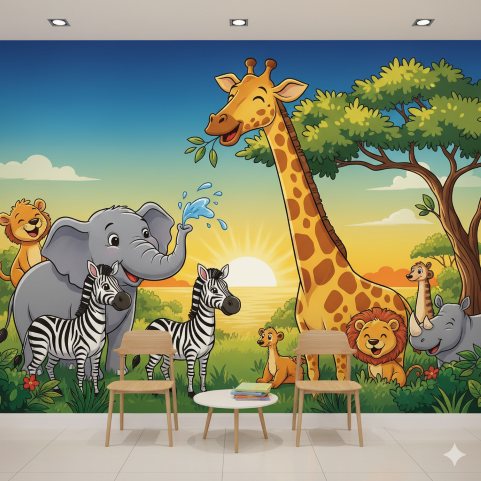

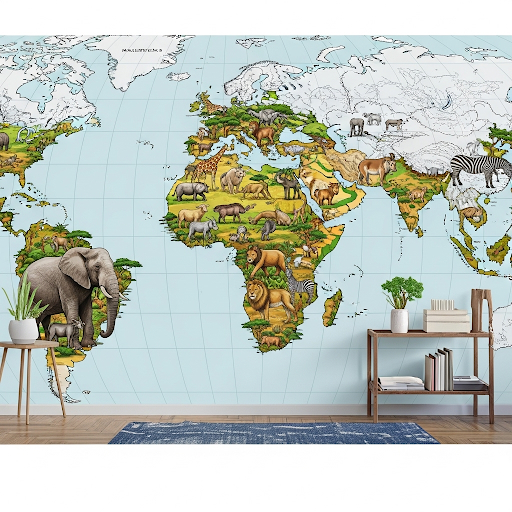

4. The Contemporary African Mural Art: Digital Wallpaper Murals

This era marks the dematerialization of the canvas. The wall is no longer a surface to be physically painted on, but a destination for a digital file. This shift from pigment to pixel has transformed African muralism from a localized craft into a globally exportable luxury product.

Here is an exposition on how the digital age is reshaping African mural art.

Afrofuturism: The Ancient Future

Afrofuturism is not merely a style; it is a philosophy that reclaims the timeline of African development. In the context of digital murals, it rejects the colonial trope of Africa as “primitive” or “stuck in the past.” Instead, it visualizes a high-tech future that is distinctly African, not Western.

The Aesthetic:

Designers blend the organic with the synthetic. You might see a Maasai Shuka pattern that dissolves into a circuit board, or a traditional Benin Bronze bust wearing a VR headset.

The Narrative:

It answers the question, “What if African development had never been interrupted?” This style is incredibly popular in tech hubs (like Nairobi’s “Silicon Savannah”) and modern corporate offices because it projects innovation while honoring roots.

The “Black Panther” Effect:

The global success of the Wakanda aesthetic normalized the blend of African tradition and advanced technology in interior design, creating a high demand for murals that feel regal, technological, and African simultaneously.

Digitized Heritage: Vectorizing Culture

This is the technical preservation of history. For centuries, patterns like the Shoowa velvet (Kuba cloth) of the DRC or the Kente of Ghana were laborious, hand-woven textiles. Today, they are being “vectorized.”

From Imperfect to Infinite:

Traditional hand-painting or weaving has natural imperfections and limits on size. By converting these designs into Vector Graphics (mathematical formulas rather than pixels), designers can scale a 2-inch piece of fabric to cover a 50-foot hotel lobby wall without a single pixel of blurriness.

Cultural Archiving:

This process creates a “digital archive” of African design. A Ndebele geometric pattern, once confined to a mud wall in South Africa (which washes away with rain), now exists as a permanent digital asset that can be reproduced in Tokyo or New York.

The Texture Challenge:

The goal of high-end digital printing is often to simulate the feeling of the original. Advanced scanners capture the topography of brushstrokes or fabric weave, so even though the wallpaper is flat vinyl, it visually mimics the depth of woven raffia or chipped paint.

Customization: The Mutable Masterpiece

In the eras of Rock Art or Street Art, the image was static. Once the paint dried on the cave wall or the concrete underpass, it was final. Digital murals have introduced the concept of the “Living File.”

Color Grading:

A designer can take a traditional warm-toned Savannah scene and “cool” the temperature to match a corporate office’s blue branding. The cultural motif remains, but the palette becomes subservient to the interior design.

Spatial Composition:

Unlike a physical painting that might get cut off by a door frame or a window, digital murals are “composed” for the specific wall. Elements (like a baobab tree or a geometric border) can be dragged and dropped in the software to ensure they sit perfectly between architectural features.

Material Versatility:

The same design file can be printed on:

Textured Vinyl:

For high-traffic corridors (washable).

Silk/Textiles:

For luxury master bedrooms (acoustic softening).

Glass Film:

For office partitions (translucency).

Summary Timeline

| Era | Rock Art | Traditional | Street Art | Digital Wallpaper |

| Primary Goal | Spiritual Connection | Cultural Identity | Political Voice | Aesthetic & Lifestyle |

| Key Tool | Stone & Ochre | Clay & Brushes | Spray Cans | Software & Printers |

| Permanence | Eons (if preserved) | Seasonal (re-painted) | Temporary (painted over) | Removable / Reusable |

| Audience | The Spirits / Clan | The Community | The Public | The Private Owner |