Description

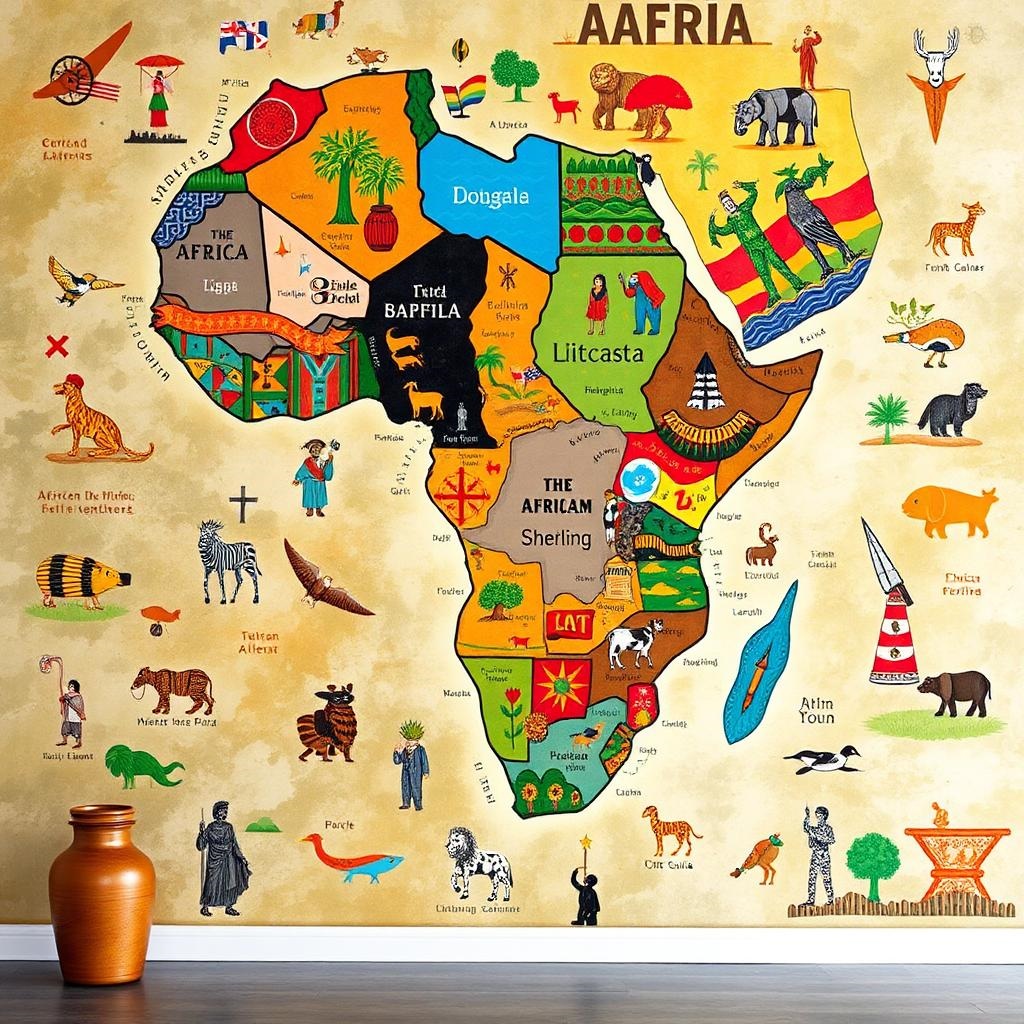

African mural themes comprise a vast visual language where every line, color, and creature serves a function. It is rarely “abstract” in the Western sense; rather, it is a codified system of communication that governs spiritual protection, social hierarchy, and moral philosophy.

Here is a breakdown of the major themes and symbolism found in African murals, ranging from ancient spiritual conduits to modern status symbols.

1. Spiritual & Cosmological African Mural Theme

This is a profound and visually striking African Mural Theme. In the context of mural art, the Ethiopian Orthodox “Winged Head” is one of the most distinct and recognizable depictions of sacred guardianship in African mural art history.

The Visual Motif: The Winged Head

In Ethiopian iconography, these figures are not merely decorative; they are theological statements rendered in paint. Visually, they are distinct from European angelic depictions. They typically feature:

A Disembodied Head

Representing pure intellect and spiritual presence, unburdened by the physical needs of a body.

Prominent, Wide Eyes

The pupils are often large and dark, emphasizing the act of “seeing.”

Wings

Usually surrounding the head, signifying their celestial nature and ability to move instantly between the physical and spiritual realms.

The Divine Omnipresence African Mural Theme

The statement that these figures represent “Divine Omnipresence” is rooted in the concept of the all-seeing eye of God.

The Unbroken Gaze

In a mural setting, particularly on a ceiling or high wall, the repetition of these faces creates a sensation that there is no corner of the room hidden from the divine gaze. Unlike a singular portrait that looks at one spot, a field of these winged heads creates a “panopticon of grace”—a sense that the divine is witnessing every action and thought within the space.

The “Thin Place” Dynamic

By covering the surface with these eyes, the wall ceases to be a barrier of stone or plaster. Instead, it becomes a window. The viewer is not looking at a wall; they are being looked at by the spiritual world. This reverses the traditional role of art; the viewer becomes the subject of the artwork’s gaze.

Symbolism: The Angelic Orders

The Nature of the Beings (Cherubim and Seraphim)

While often simply called “angels,” these winged heads specifically reference the Cherubim and Seraphim—the highest orders of angels who reside closest to the Divine Throne.

Cherubim

Traditionally associated with infinite knowledge and wisdom. Their varying directions of gaze symbolize that God’s wisdom encompasses all perspectives—past, present, and future.

Seraphim

The “burning ones,” associated with light and ardor. Their presence on a wall implies that the space is charged with spiritual heat and purity.

The Ceiling of Faces (Debre Berhan Selassie)

The most famous iteration of this is the ceiling of the Debre Berhan Selassie Church in Gondar, Ethiopia.

The Cloud of Witnesses

The repetition of faces (often numbering in the dozens or hundreds) represents the biblical “cloud of witnesses.” It suggests that the spiritual realm is populous and active.

Infinite Multiplicity

The sheer number of faces symbolizes the infinite nature of God’s attributes. No single face can capture the Divine, so the artist uses a multiplicity of faces to suggest the limitlessness of the Creator.

Protective Function: Guarding the Sacred Space

In the Ethiopian tradition, the church building mirrors the Temple of Solomon. The “Holy of Holies” (the inner sanctum) must be guarded.

Spiritual Sentinels

Just as physical guards watch the gates of a city, these winged heads watch the “gates” of the spiritual realm. Their wide-eyed stare is vigilant. They are there to spot and repel “demonic entry”—which, in a psychological or spiritual sense, can represent negative energies, distraction, or evil intent entering the mind of the worshipper.

Sanctification of Space

By painting these figures, the artist claims the space for the Divine. A wall bearing these images declares, “This territory is under the jurisdiction of Heaven.”

Summary for Mural Application

If you are applying this theme to a modern mural project, you are essentially creating a “Canopy of Protection.”

Aesthetic

It utilizes rhythmic repetition and pattern, which is visually soothing yet intense.

Atmosphere

It cultivates a sense of accountability and safety. The viewer feels “watched over” in a benevolent sense.

The Python (Igbo Uli & West African Vodun)

Theme:

Regeneration & Water.

Symbolism:

The python is revered as a messenger of the water spirits. On a wall, a wavy line or snake motif often symbolizes the rainbow (the python’s reflection), representing wealth, rain, and the cyclical nature of life (shedding skin).

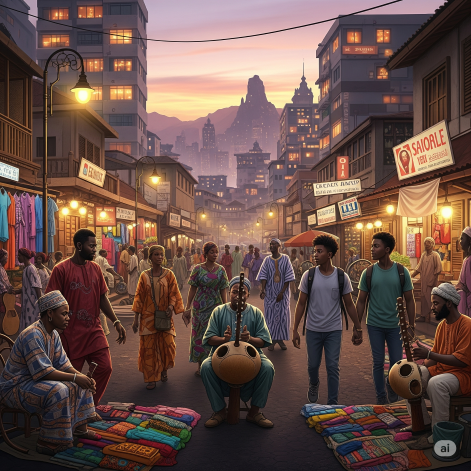

2. Social Status & Architecture of Intimacy

African Mural Themes often act as a public resume or a private sanctuary, defining who is allowed to enter specific spaces.

The “Niche” (Vidaka – Swahili Coast)

Theme: Wealth & Cosmopolitanism

The vidaka represents the homeowner’s connection to the vast Indian Ocean trade network. Displaying imported treasures within these architectural cavities signaled sophistication and economic power. It was a visual assertion that the household was not isolated, but a cosmopolitan player in a global exchange of goods and culture.

The Architecture of Display

Unlike flat murals, the Swahili wall is three-dimensional. The deep, multi-tiered niches (often spanning entire walls in a grid called zidaka) turn the wall itself into a gallery. This serves a dual purpose: structural cooling and aesthetic storage.

Porcelain as Currency

The “imported porcelain” mentioned is crucial. In the 18th and 19th centuries, owning Chinese porcelain or Persian ceramics was the ultimate status symbol. The wall was built literally around these objects; the architecture existed to serve the collection.

The Ndani (Inner Sanctum)

The placement of these intricate walls in the Ndani (the innermost bedroom) is significant. It suggests that true wealth is not for public showboating, but for the private enjoyment of the family and the consummation of marriage. It creates a “sanctuary of sophistication” where the intimacy of the couple is framed by the evidence of their success.

The Triangle & Diamond (Ndebele – South African Mural Themes)

Theme: Female Virtue & Marital Status

This mural tradition is a matriarchal code, where the home’s exterior serves as a billboard for the female head of household. The designs act as cultural identifiers, celebrating rites of passage, marital fidelity, and the continuity of tradition, transforming the mud wall into a vibrant statement of resilience and identity.

The Language of Geometry

The Ndebele wall is not abstract art; it is a language. Specific patterns can indicate whether a woman is married, if her son is undergoing initiation, or if she has many children. The wall speaks to the community on her behalf.

Precision as Virtue

The “diligence” mentioned refers to the crispness of the lines. In a context where tools were traditionally simple (feathers or fingers) and canvas was mud, achieving a perfectly straight line was a demonstration of immense skill and discipline. A sloppy wall implied a sloppy home.

The Razor Blade Motif

The “Triangle & Diamond” often mimics the shape of a razor blade (a common gift in Ndebele courtship). This sharp geometry protects the home, symbolically cutting away negative influences while broadcasting the sharpness and capability of the matriarch.

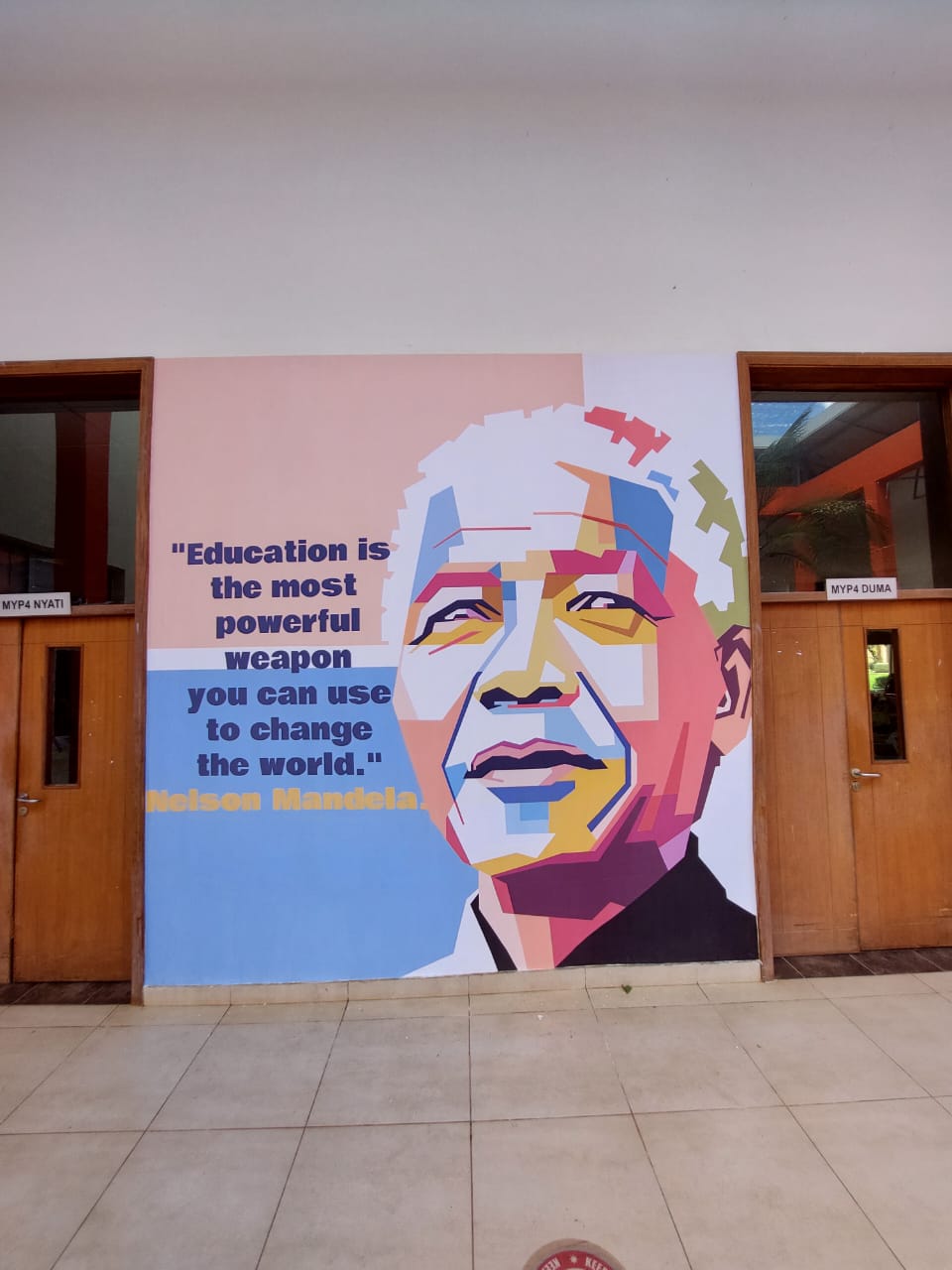

3. Ethical & Philosophical African Mural Themes

Some African mural themes function as large-scale textbooks, teaching moral lessons to the community.

Beauty as Morality (Igbo Uli)

Theme: Atu (Design/Pattern)

Uli is a linear mural art form defined by delicate, curvilinear patterns and a masterful use of negative space. Drawn with ephemeral indigo dye, these motifs—abstracting cosmic and natural elements—are temporary, mirroring life’s cycle. The mural designs transform architecture into living canvases, emphasizing fluidity, balance, and the necessary impermanence of beauty.

Symbolism

In the Uli tradition, the act of painting itself is moral. The Igbo concept Nma translates to both “beauty” and “goodness.” A wall painted with Uli (curvilinear abstract forms derived from plants and animals) declares that the house is morally upright and harmonious with nature.

The Sankofa Bird (Akan – Ghana)

Theme: Hindsight & Wisdom

This African mural theme centers on the critical importance of learning from the past to secure the future. It rejects the idea that looking back is regression; instead, it positions historical knowledge as the essential foundation for progress. The imagery serves as a constant visual prompt to reclaim lost heritage and correct past mistakes before moving forward.

Symbolism

Often depicted as a bird turning its head backward to groom its feathers (or taking an egg from its back). On walls, this reminds the community that “it is not taboo to fetch what is at risk of being left behind”—a call to remember ancestral wisdom while moving forward.

4. Nature as Totem (Zoological African Mural Symbols)

Animals in African murals are almost always metaphorical, representing human traits or clan lineages.

5. Color Symbolism in African Mural Themes

Before synthetic paints, colors were ground from earth, linking the mural directly to the land.

Red (Ochre/Camwood):

Meaning: Transition & Life Force.

Red is the color of blood (life), the earth, and danger. It is often used to mark thresholds (doorways) to protect against spirits or to celebrate a rite of passage (like initiation).

White (Kaolin/Chalk):

Meaning: Purity & Spirit.

White is the color of the ancestors and the spirit world. White clay on a wall often indicates a sacred space, a shrine, or a place of peace where truth must be spoken.

Black (Soot/Charcoal):

Meaning: Maturity & Secrecy.

Black often represents age, wisdom, and the “cooling” of emotions. In geometric art, black lines “contain” the energy of the other colors, representing order and stability.

Indigo Blue:

Meaning: Wealth & Sky.

Historically an expensive dye, blue on a wall (common in West African Mural Themes and the Yoruba tradition) is a status symbol connecting the home to the sky and the water deities (like Yemoja).